Exploring the “Kyōto Komonjo” Scrolls

By Daniel Botsman

Before taking up his faculty appointment at Yale in 1907, Kan’ichi Asakawa returned home to Japan for a year and a half, in part so that he could begin collecting research materials for the university library. One of the important acquisitions he made during this extended trip home was a set of Edo period (1600-1868) documents known simply as the “Kyōto Komonjo” or “Old documents from Kyoto” . The items in the collection concern an event known to historians as the “Town Deputies’ Reform Incident” (chōdai kaigi ikken). This incident, which began in the summer of 1817 and continued for a full eighteen months, formed part of a long struggle by commoner residents of Kyoto to assert greater control over the management of their own affairs. It led to a major re-organization of the machinery of local government and the formation of new institutions called the “Great Assemblies” (Ōnaka), in which representatives of the city’s neighborhoods were able to come together to deliberate and determine various aspects of urban administration. For this reason, it is considered a crucial moment in the development of Kyoto’s modern political culture and an important example of commoner political mobilization in the decades prior to Japan’s “opening” to the West.

Two large scrolls form the centerpieces of Yale’s “Kyōto Komonjo” collection. The first scroll, a full English translation of which we hope to make available on this website at a future date, contains the “Statement of Resolution” (Osorenagara sumi shōmon) prepared for submission to Kyoto’s Town Magistrates at the conclusion of the incident in 1818. It carefully details the accumulated grievances that led representatives of Kyoto’s Neighborhood Federations (chōgumi) to launch a city-wide protest against the authority of the Town Deputies (chōdai)—a small group of commoner officials who served as intermediaries between Kyoto’s ordinary residents and their samurai governors. It not only allows us to better understand what was at stake in the dispute, but also offers a window into various aspects of urban life in 19th century Kyoto—including its complex hierarchies of status and power.

This is equally true of the second scroll, titled “In Celebration of the Return of the Revered Documents” (Taibun saikan iwai), which can be examined in detail here. At almost 17 meters (approx. 55 feet) in length, it features a detailed painting of a triumphal procession through the streets of Kyoto that took place at the end of 1818, late at night after the city’s samurai governors had issued their final ruling in the dispute. A similar scroll has been preserved in Kyoto as part of a collection of documents in the possession of the Hisamatsu family, but the Yale scroll has several distinguishing features, including two passages of explanatory text, which we have transcribed and translated into English. The second of the passages, appearing at the very end of the scroll, is especially noteworthy: It bears the formal signature (ka-o) of a man named Ishiguro Mitsunori and clearly states that it was he who commissioned the scroll in 1821 (Bunsei 4), several years after the procession took place. This is significant because Ishiguro, who appears in official documents under his common name, Tōbei, was the leader of the first group of commoner protesters to trigger the campaign against the Town Deputies in the summer of 1817.

But why did the procession take place in the first place? And why was Ishiguro so keen to preserve its memory for posterity?

As the text of the 1818 “Statement of Resolution” makes clear, most of the complaints that Ishiguro and his allies across the city came to levy against the Town Deputies had to do with their day to day conduct and management of local affairs. From early on in the dispute, however, they also claimed that the Deputies were improperly in possession of a number of important documents issued by Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, the great warlords who laid the foundations for the country’s Great Peace. These “revered documents” (taibun), bearing the same vermillion seals (goshuin) as the formal investiture documents that confirmed the authority of the country’s Daimyō lords, had been addressed to the people of the city’s chō neighborhoods. For this reason, the question of who should be in possession of them was intimately connected to the larger issue of who had the right to represent the neighborhoods in dealings with the samurai authorities.

Unlike modern city neighborhoods, the chō were not simply spatial units. At root, they were associations of local property owners, formed by the artisans and merchants who lived and ran their shops together, typically along two sides of a short stretch of one of the city’s streets. At least originally, households engaged in the same trade would often cluster together in a single chō, a fact that was reflected in many of the neighborhood names. Ishiguro Mitsunori, for example, was the Elder (toshiyori) for Kamanza-chō, which, as its name suggests, was originally home to the city’s venerable “guild of kettle makers” (kamanoza). Because the heads of Edo period households were almost always male, the formal affairs of the chō fell under the exclusive control of men, even though the residents of the neighborhoods naturally included significant numbers of women, as well as children, and propertyless men (renters, servants etc) who were similarly excluded.

One of the important functions of the chō had always been to police the streets and maintain order so that commerce and trade could flourish within. For this reason, the physical boundaries of the chō were usually marked by a set of wooden gates (kido) that could be guarded and closed off at night or in times of emergency. One such set of gates, at the border between the neighborhoods of Oike-no-chō and Enpukuji-chō, can be seen clearly in the first panel of the painting on the Yale scroll.

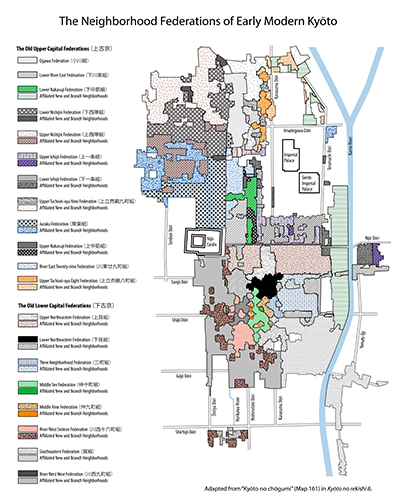

There were, of course, limits to what any one, small neighborhood could do to police and protect itself. During the chaos of the Warring States period (1467-1600), therefore, when the city was continually threatened by various forms of conflict and strife, groups of neighborhoods began to form broader alliances for purposes of self-defense. This was the origin of the city’s Neighborhood Federations (chō gumi). Over time, these Federations also organized themselves into even larger groupings called Consolidated Districts (sōchō), giving rise to a three-tier organizational structure (chō – chōgumi – sōchō, i.e. neighborhood – federation – district). Although there were officially five Consolidated Districts, by far the most important were the Lower Capital (shimgyō) District in the South and the Upper Capital (kamigyō) District in the North, which together accounted for some 1454 of the city’s 1547 chō neighborhoods. These two Districts were dominated by the oldest of the city’s Neighborhood Federations (eight in the Lower Capital, twelve in the Upper Capital) but gradually came to incorporate large numbers of “new” and “branch” neighborhoods, creating an immensely complex set of hierarchies and relationships. Some sense of this complexity is captured in the map to the left, which shows the areas of the city covered by the various Neighborhood Federations.

During the dispute with the Town Deputies, Neighborhood Federations from both the Upper Capital and the Lower Capital Districts joined forces to express their grievances and, in the process, make the case that they were the rightful owners of the “revered documents” issued to the people of the city by Hideyoshi and Ieyasu. Indeed, according to the Neighborhood Federations, the Town Deputies had originally been lowly servants, who had then gradually came to arrogate more and more power to themsleves as a result of their interactions with the samurai authorities. As Sugimori Tetsuya has shown, the historical record, in fact, suggests a far more complex genealogy. But during the course of the formal investigation of the complaints levied against them, the Town Deputies were ordered to surrender the “revered documents” for official review, and at the conclusion of the case, the Magistrate ruled that they should be handed over to the Neighborhood Federations. This decision to “return” the revered documents was rightly understood at the time as signalling a complete triumph for the Neighborhood Federations in their dispute with the Deputies. As a result, when representatives of the Federations were summoned to collect the “revered documents” from the Eastern Town Magistrate’s Offices in the middle of the night, the affair quickly took on the air of a victory parade. It was this moment of celebration that Ishiguro sought to capture in the scroll and it is not difficult to understand why it was of particular importance to him.

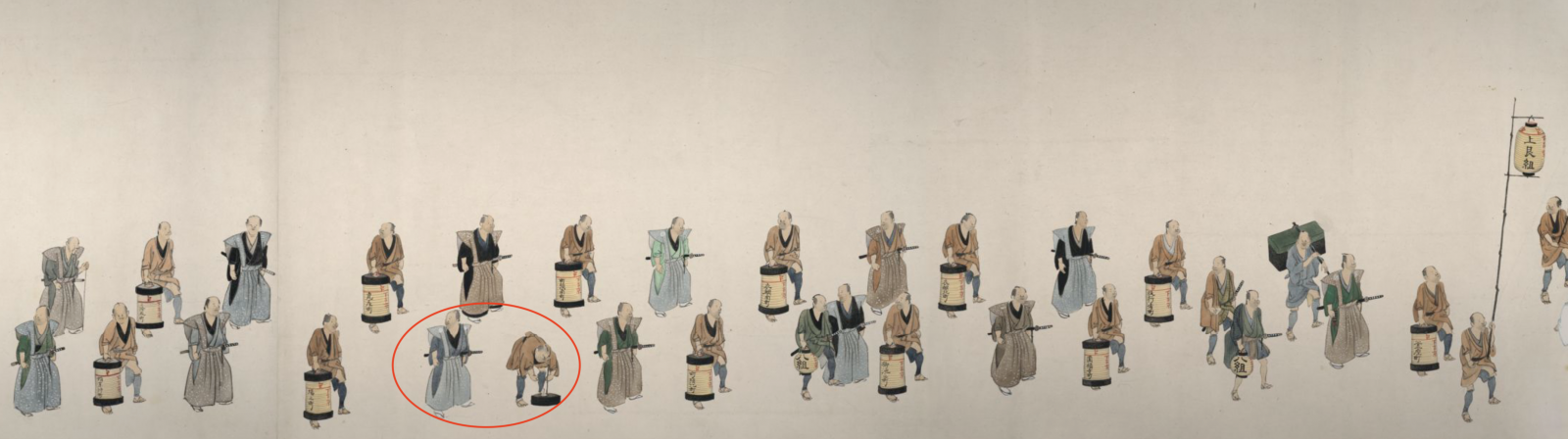

As the scroll makes clear, although Neighborhood Federations from both the Upper and Lower Capital districts had joined forces in the campaign against the Town Deputies, it was the Federations of the Lower Capital that were first summoned to receive the “revered documents” at the conclusion of the case. This was because in the summer of 1817, it had been a group of chō representatives from the Lower Capital’s Upper Northeastern Federation (Kami ushitora-gumi), who had intiated the dispute by presenting a formal letter of complaint to the Town Magistrates. Ishiguro Mitsunori had led this group. Not surprisingly, then, he is depicted in the scroll in a clear place of honor, walking at the head of the other neighborhood Elders from the Upper Northeastern Federation immediately behind the “revered documents”. These are shown being carried in a special chest, cloaked in decorative cloth, by a group of men in white ceremonial robes, who, according to the note at the beginning of the scroll, had been dispatched hurriedly from the famous Yasaka Shrine in Gion. A sign indicates that the documents inside bear the vermillion seals of the great lords, with a vermillion umbrella, traditionally reserved for persons of high status, offering an additional reminder of their exalted provenance. More chests, containing less important documents can also be seen trailing along at the very end of the procession.

In making sense of what is depicted in the scroll, the lanterns shown are especially important because they indicate the affiliations of those marching behind them. The lanterns at the front of the procession announce that those who follow represent the Eight Federations (hachikumi) of the Old Lower Capital District. After Ishiguro and other representatives of the Upper Northeast Federation we see neighborhood Elders from the Middle Nine Federation (Naka kyūchō gumi), the Middle Ten Federation (Naka jūcchō gumi), the Three Neighborhood Federation (Sanchō gumi), the West Bank Nine Federation (Kawanishi kyūchō gumi), the Lower Northeastern Federation (Shimo ushitora gumi), the West Bank Sixteen Federation (Kawanishi jūroku-chō gumi), and the Southeast Federation (Tatsumi gumi). These were the original Eight Federations of the Lower Capital. But they are followed in the procession by five other Federations representing “new”or “branch” communities. In a subtle, but clear, sign of the status differential that existed between the two groups, the lanterns of these new Federations indicate simply that they belonged to the Lower Capital District (shimo gyō), whereas the lanterns of the original Eight Federations include an extra Chinese character to remind all concerned that they represented the Old Lower Capital (shimo ko-gyō).

Even among the original Eight Federations, Ishiguro’s Upper Northeastern Federation is the only one in which the individual names of constituent chō neighborhoods are also indicated on lanterns. Indeed, the only reason we know that it is Ishiguro at the front of the group is because of the lantern bearing the name of his neighborhood—Kamanza-chō. Behind him there are eleven other lanterns bearing the names of individual chō, as well as one additional lantern that cannot be read because it has yet to be unfurled. This is significant because although the scroll depicts a total of thirteen neighborhood Elders in the Federation, only twelve (including Ishiguro) had gone to the Magistrate’s Offices to present the original letter of complaint at the beginning of the dispute in 1817. More than artistic whimsy, then, it seems likely that the unfurled lantern in the scroll was intended as a deliberate act of censure against the neighborhood Elder from Ryōgae-chō (later renamed Kakimoto-chō) who failed to support his peers in their moment of need.[1] Although more work needs to be done to confirm the details, the scroll may well contain other messages of this kind, indicative of Ishiguro’s general sense of who had been reliable allies in the campaign against the Town Deputies. It is surely no coincidence, for example, that representatives of the Southeast Federation (Tatsumi gumi), whose leaders were initially reluctant to join the campaign against the Town Deptuies, are shown marching last among the original Eight Federations.

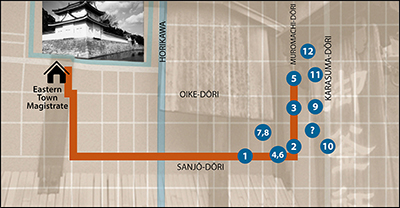

One final reason why Ishiguro may have been particularly keen to preserve the memory of procession has to do with the route that it followed. As explained in the text at the beginning of the scroll, after receiving the “revered documents” from the Eastern Town Magistrate’s office, the assembled group first proceeded south for a few blocks before turning east onto Sanjō-dōri (street), which it then followed until reaching Muromachi-dōri. Here the group turned north, proceeding as far as the neighborhood of Oike-no-chō, where it had been decided that the documents would initially be stored.

As shown in the map,  this U-shaped route took the procession through the heart of most of the Upper Northeastern Federation neighborhoods, including, most notably, Ishiguro’s home of Kamanza-chō. And, if the depiction in the first panel of the painting is to be trusted, it would seem that the entire population of the area, men and women, young and old, turned out to bear witness to the arrival of the “revered documents.” In this regard, too, it was clearly remembered by Ishiguro and his allies as a moment of public vindication and relief, after the tense, 18-month struggle against the Town Deputies—the outcome of which had remained uncertain until the very end.

this U-shaped route took the procession through the heart of most of the Upper Northeastern Federation neighborhoods, including, most notably, Ishiguro’s home of Kamanza-chō. And, if the depiction in the first panel of the painting is to be trusted, it would seem that the entire population of the area, men and women, young and old, turned out to bear witness to the arrival of the “revered documents.” In this regard, too, it was clearly remembered by Ishiguro and his allies as a moment of public vindication and relief, after the tense, 18-month struggle against the Town Deputies—the outcome of which had remained uncertain until the very end.

In 2018, exactly two centuries after the procession depicted in the Yale scroll first took place, members of the “Kyōto Komonjo” study group were able to re-trace its route through the streets of the city during a special Summer Retreat for graduate students sponsored by Yale’s Council on East Asian Studies. As this carousel of images shows, the streetscape of the ancient capital has changed profoundly since Ishiguro’s time, most obviously as a result of the need to accomodate the modern automobile. More than in most Japanese cities, however, clear reminders of the past do still abound in Kyoto, including in Kamanza-chō, where an old wooden sign advertising the services of a kettle maker (kama-shi) still hangs prominently in the middle of the neighborhood.

[1] In his authoritative study of the Neighborhood Federations, Akiyama Kunizō lists a total of 14 chō neighborhoods as having belonged to the Upper Northeastern Federation. Akiyama, Kinsei Kyōto Chōgumi Hattatsu-shi (Toyko: Hōsei Daigaku Shuppankyoku, 1980), p. 284. Of these, the two neighborhoods whose names do not appear on the lanterns in the procession are Ryōgae-chō and Koromodana Tsukinuke-chō. It seems likely that the latter of these was represented by either the North or South Koromodana-chō Elders who are clearly shown in the procession. This leaves Ryōgae-chō as the most likely target of the unfurled lantern.